Our story is not just about wars and blood.

At the end of the millennium, the fatal passage of the Apocalypse that can be summed up in the sentence: "One thousand and not more than one thousand" spreading a general terror for the imminent end of the world, induced the most fearful and sinful landowners to book a place in Paradise by paying generous oblations to Religious Orders, determining their development which led to the founding of the first Benedictine monasteries on the Riviera around the year 1000.

Since that time began here the cultivation of the olive tree (already present in our area) under the material and spiritual guidance of those hard-working monks who seriously lived their strict rule of "Ora et labora" (pray and work)(1).

An immense work, tenaciously pursued for centuries with the progressive deforestation of the woods and the terracing of the impervious and rocky terrain.

The continuous struggle between bishops and counts favored, on the Ligurian coasts, the formation of "compagne": associations of free men, plebeians and nobles, who - thanks to their economic power - favored the creation of the "Commune". Thus a new scenario was created: in the hinterland the feudal lords continued to administer the territories from their castles, on the coast the Communes carried out an autonomous political and economic life.

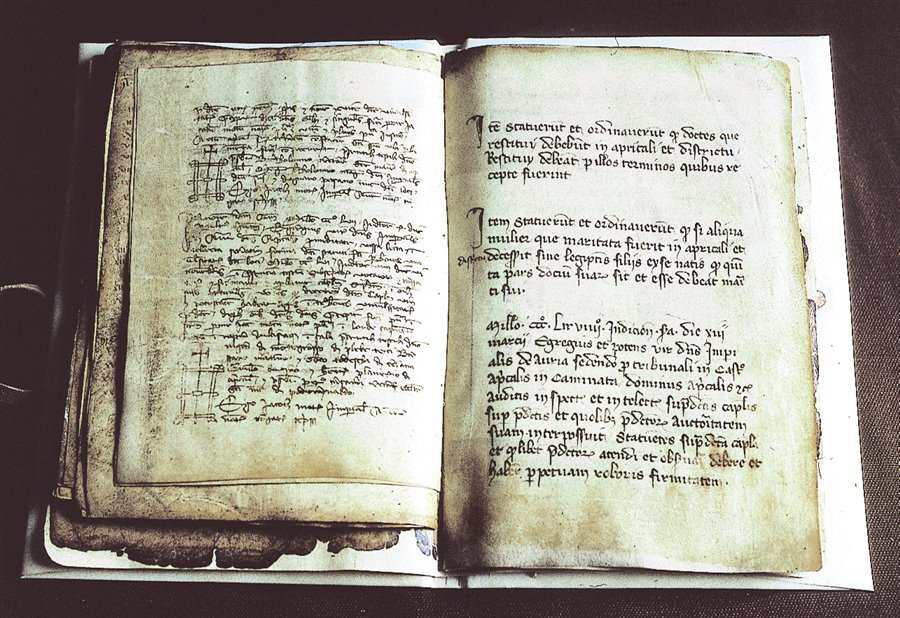

In the thriving villages of the Riviera, then, not only economic conditions but also social conditions improved: among other things, people finally succeeded in obtaining the Statute from the local feudatory, the first form of written codification of civil and criminal laws(2).

This is the era in which in every town the internal struggles have been resolved with the affirmation of the richest and most unscrupulous family that, having got rid of internal competition and having acquired dominion over the village, began to look beyond the walls in the ravenous search for new possessions that could increase their wealth and power, perpetually inadequate to the ambition that sustained them.

From the year one Thousand onwards, to the powerful ecclesiastical pole represented by the Bishops of Albenga and Ventimiglia, but above all by the Archbishop of Genoa, on the one hand opposed the growing power of the Republic of Genoa, and on the other the affirmation of the most enterprising local Lordships in an extremely varied and composite mosaic.

The extreme west was in the hands of the Counts of Ventimiglia who also dominated the Maro valley. The ferocious Dorias made bloody raids all around their base in Dolceacqua. From their strongholds of Pieve di Teco and Prelà, the ubiquitous Clavesanas expanded in the Impero valley and in the Diano area on one side, and towards the west on the other.

The Del Carrettos pressed from the east, the Lascaris looked out from Brig and moved to Pantasina and the Maro valley, the Grimaldis of Monaco infiltrated from the west. The Spinolas and the Dorias made deals in Genoa and the Lengueglias stretched their hands from San Lorenzo.

To western Liguria also aspired much more distant powers such as the Milanese Viscontis and Sforzas (often Lords of Ventimiglia) or the neighbors Savoys who stubbornly bought and then defended every piece of land that brought them closer to the sea; from Provence, the d'Anjous (first the two Charles and then Robert) tried several times to even annex the whole area.

The titanic clash between empire and papacy allowed bishops, counts and marquises, of whom west Liguria abounded, to play with alliances and conspiracies that determined the succession of sales and armed clashes between the different “Signorie”, engaged in the inexhaustible undertaking of enlarging their domains and at the same time nullify the analogous claims of others(3).

All the towns of the Ligurian west underwent repeated buying and selling in a gigantic Monopoly game that determined intricate bundles of disputes that often slided from the judge's table to the battlefield, involving not only those directly interested but also their respective allies (with the corollary of their neighbors), each with their own claims to assert(4).

As it always happens, a powerful external force capable of carrying out a credible arbitration action in local disputes ended up securing the dominion over all: and it is precisely following the always valid policy of "divide et impera" that Genoa intervened as peacemaker in the continuous skirmishes of the coastal feudal lords divided between the Guelphs (the Counts of Ventimiglia, the Grimaldis, the Ventos) and Ghibellines (the Dorias and the Spinolas). And, as it happens, the "arbitration award" of its magistrates always sided for that feudal lord who first swore allegiance to the Republic.

When the stamps were not enough, in its race to the role of great power Genoa did not hesitate to resort to weapons, crushing with violence every resistance as it did with the heroic Ventimiglia - then its fearsome rival allied with Pisa – which was attacked and conquered a first time in 1140, then in 1222 and definitively defeated and subjugated(5) in 1477 after centuries of bloody wars of aggression.

Varigotti was also an important seaport, equipped with a castle, with a beautiful harbor active since Roman times, later expanded under the Marquises Del Carretto; a port so important that it was among other things, in 975, the center of collection of all Christian galleys departing for the victorious siege of Frassineto. In 1341, Varigotti passed under Genoa, which, as a first provision, ordered the burial of the port (which disappeared forever in the sand), so that another flourishing emporium on the Mediterranean, rich in commerce and prospects, was suddenly reduced to a village without future.

The fate of Savona will not be different, as it will pay dearly for being "very flourishing in maritime trade to the detriment of the capital". In 1525, Genoa attacked it and conquered it, and the doge Antoniotto Adorno not only imposed the insult of compensation of war damages in the sum of twenty-five thousand gold “scudi” (i.e. the currency of the time), but also here ordered the complete burial of the port (which could be restored only two centuries later) ".. to remove its trades, since it is not possible to fly for a bird without wings" as cynically commented by Agostino Maria De Monti. And thus, even Savona's great potential "flight" over the sea was cut off forever.

Genoa continued to fatten up visibly by sucking the blood of the sister cities of the Riviera: from each subjugated town, it not only squeezed every financial resource by taxing them, but to tear apart any possible future rivalry it immediately started their economic dismantling by drastically reducing every commercial activity and above all by cynically destroying any mercantile potential.

Anyone who tried to rebel ended up like Sanremo, which refused to pay the Genoese taxes that were strangling the city: Genoa immediately sent its army to besiege the city which, after solemn promises of safety, surrendered. The winners, however, as soon as they entered Sanremo, hanged all the rioters, ruined the castle of Pigna, severed the bell tower of San Siro, taking the bell to Genoa, imposed heavy payments on all the heads of the families, tightened even more the brakes to any form of trade and, on the port, built and occupied the fortress of Santa Tecla, which still today points threateningly not towards a potential external enemy, yet towards the city its loopholes, armed with powerful guns.

Few examples like this will be enough for Genoa to be in a favourable position in proposing offers that no one could refuse, and therefore buy for nothing cities(6) and castles of the feudal lords who, after having sworn allegiance to the Republic, remained in their place in a state of total subjection, de facto debt collectors on behalf of Genoa, but gratified by the prudish official status of "allies".

In addition to taxes and trade restrictions, then, each subjugated city suffered the beheading of the towers and the drastic reduction of each fortification.

Traces of Genoese cynicism are practically in every suburb of the Ligurian west:

- in 1203 the army of Genoa "... went to Tabia (Taggia) and completely destroyed the castle";

- in 1204 "... demolished two castles, which had been fortified by the villains of Val d'Arosia and of Unegia"; "Fulcone went to the area of Vintimilio - it is written in the Annals of 1239 - in the place called Santo Ampelio, where the men of Vintimilio, traitors of the Municipality of Genoa, had gone; and there was a great battle, in which many from both parts were wounded to death and killed. Finally the mentioned Fulcone and the Genoese who were with him prevailed in fighting and demolished the tower of Santo Ampelio and the houses and shelters of the foreigners of Vintimilio and destroyed and devastated the lands... ";

- in 1340 "some noble Dorias attacked the castle of Pietralata (Prelà), which was held for the community, and killed the whole guard of the castle and destroyed it to its foundations";

- in 1341 the doge Simon Boccanegra had the fortress of Castellaro, near Tabia, "destroyed to its foundations";

- in 1405 Genoa ruined the castle of Pornassio, acquired with an "arbitration award" twenty years before; and so on, demolishing the whole Riviera.

In fact, in order to make money, Genoa did not hesitate to put into play the very life of its subjects who, deprived of any defense, would not dare to rebel in the first place; but above all who, to repel the aggressions of third parties (and here also the "Turks" will be advantageous to Genoa; and it is not surprising therefore the release of the terrible Dragut by the Dorias ...), would depend totally on the whim of their stepmother who stretched out cynically, depending on the "loyalty" of the applicant (i.e. on the amount of taxes they are willing to pay), sometimes the authorization to build a tower(7), sometimes the dispatch of an armed galley. Everyone would therefore bite every bullet to keep Genoa good.

And there are many bullets to bite, among taxes of every kind, drastic limitations to every activity and continuous call-ups of men, taken from home to be thrown in arms on the galleys to support the centuries-old, harsh war that Genoa wages to the rival Maritime Republics of Pisa, Amalfi and Venice pursuing its great design of commercial monopoly over the whole Mediterranean.

On the threshold of the fourteenth century, bleeding and strangling one by one all the sister cities of the coast, Genoa had secured direct or indirect control (through the local feudatory) over the entire Ligurian west and could therefore finally set up, with the decisive obligatory participation of men and ships from all the coastal towns, the great fleet that in 1284 defeated at Meloria the rival Republic of Pisa ("of the Pisans was made such great massacre - tell the chronicles of the time - that everywhere the sea appeared red, so much was covered with shields, oars and corpses of the dead"), conquered Cagliari in 1290 and, in 1301, beat the fleet of the Republic of Venice at Curzola.

Thus, finally risen to the rank of great power, Genoa must defend from its other rapacious peers its dominions and in particular the Ligurian west, on which – having held back the repeated expeditions of the Provençal of Anjou throughout the 12th century - were now getting more threatening the expansionist aspirations of the Savoys who at all costs wanted a place in the sun and persistently pursued this design over the centuries.

The first exit to the sea was acquired by the Savoys in 1391 with Amedeo VII taking possession of Nice; then, in 1425, Briga and Tenda were subdued, counties that the Savoys later acquired definitively from the Lascaris in 1575 together with the lordship over Maro and Prelà. In addition to money, the Piedmontese also resorted to low blows, as in 1451 when they sent the brigand Giovanni Benedetto of Sospello to occupy Olivetta San Michele with a gang of one hundred and sixty delinquents (who would however be sent away the next year by Enrichetto of Dolceacqua).

In 1576, the duke Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy with a masterstroke cut the Genoese territory in two, buying from Gian Gerolamo Doria no less then the lordship on Oneglia, which became the capital of the Savoy province, invigorating, among other things, the centuries-old rivalry (as early as 1200) that still today opposes Oneglia to Porto Maurizio, which has always remained faithful to Genoa (and "semper fidelis" is in fact its motto on the municipal banner).

(1) On the Riviera, the Benedictines built several monasteries, but certainly the most significant social action radiated from the Dominican convent of Taggia, which was for the first five centuries after the year one Thousand the main cultural center of the Ligurian west; to that center also goes the merit of having started the cultivation of the olive tree. To witness the past splendor, today entrusted to the surviving friars are the ancient library (whose access is reserved to scholars) and the rich picture gallery with works by the Breas and other late fifteenth-century painters well exposed in the Lombard-Gothic church of S. Domenico.

(2) If the people take their first steps towards democracy, for the local lords the granting of some rights (which among other things would often remain only on paper) was worth the huge sum that is seized, a real boon to acquire new possessions by buying them or conquering them with an army enhanced with that money; also because, having granted full satisfaction to the subjects and resolved the internal tensions, the feudal lords would no longer have to deal with those who bothered them domestically and would therefore finally be able to commit themselves to go and bother someone else.

(3) To illustrate the vicissitudes of the towns of the Ligurian west we report for all the history of Vallecrosia, before the year one Thousand a fief of the Counts of Ventimiglia, then sold to Robert of Anjou and from him even to Robert King of Naples who in the fifteenth century sold it to the Republic of Genoa; from there the village passed for six thousand gold ducats to the Milanese Filippo Maria Visconti who will then sell it to the Lomellino family; in 1447 it was bought by the Grimaldis of Monaco and then by the King of France who in turn sold it in the seventeenth century to the Counts of Ventimiglia closing the circle.

(4) On the other hand, protests and disputes are practically inevitable: the repeated changes of ownership and fief are in fact real factories of troubles suitable for the best pettifogger. Take for example the case of Ranzo, owned by the Clavesanas, who in 1355 sell half of it to Emanuele Del Carretto, and three years later to Genoa the other half, of which they still remain feudal lords. Immediately the Del Carrettos make troubles, claiming that the Clavesanas should have sold to them and not to Genoa the second half of the village; the matter ends before the magistrate Antonio Adorno, whose "arbitration award" establishes that the Del Carrettos must give up three quarters of what they own to Genoa, while preserving their feudal rights. Said in this way it seems easy, but in fact now the tiny Ranzo is divided into two halves, one of which is a possession of Genoa and the feudal lords Clavesana, while the other half is for three-quarters property of Genoa and for a quarter property of the Del Carrettos, who are however also the feudal lords of the three quarters of the half-Ranzo owned by Genoa; and it is hard to divide -without upsetting anyone- the poor income of those people who form the fifty "fires" (families) of Ranzo among these ravenous "Lords", always ready to slaughter each other at the first discussion on the loot!

(5) The surrender conditions are very harsh: in addition to imposing heavy financial, fiscal and monetary sanctions, the Podestà of Genoa, Messer Martino di Sommariva "... since Count Guillermo di Ventimilio and his sons remained unfaithful and rebellious and disobedient to the Municipality of Genoa, and many felonies they committed against the Municipality of Genoa" he even deviated the course of the Roia leaving therefore dry the flourishing canal port that was at the mouth of the river, at whose entrance he also sunk a ship laden with stones to finally obstruct the access . Ventimiglia lived of that port and, thanks to it, it prospered; its destruction destroyed every prospect forever.

(6) For example, Santo Stefano is bought in 1353 for eighty gold "doppie".

(7) As it happens in Porto Maurizio for the tower of Prarola, whose construction had to be negotiated for a long time even after a terrifying raid by Dragut in 1562.