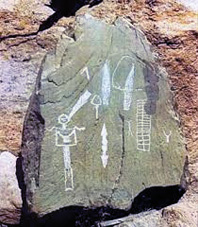

Even the Ligurians of prehistory - first nomadic gatherers, then almost nomadic hunters and breeders, finally farmers and merchants - recognized transcendent values to what was inexplicable or ineluctable to them.

On Monte Bego and at Balzi Rossi, for example, there is evidence of sacrifices to natural phenomena, such as thunders, lightnings, and death: fears and insecurities motivated the search for favors and protection. Suprahuman powers actually were also attributed to the sun, to water and to important positive functions of nature. The cult of the deads was practiced with the intention of exorcising the anxiety of the end and the caducity of life. In the oldest tombs we find, in an exclusive or pre-eminent position, masculine remains, as physical strength determined, for the survival of all, a full-blown male gender superiority. In later periods, with the advent of permanent settlements and the adoption of an agricultural economy where women and men had equal productive abilities, female remains shared the tombs.

The development, over time, of economic and civil conditions required the opening of new communication routes to facilitate trade and exchange in its various forms. The Celtic populations, for example, migrated in large numbers to the Ligurian lands in the 4th and 5th centuries BC bringing their distinctive elements. The cult of fertility is indeed of Celtic origin. At the beginning, the most important fertile function was attributed to the male, for which reason temples were built to the male god Belen (Beleno, Belenus). In Costa Balena, near Capo Don (Taggia), there are finds of a temple dedicated to this god. Worship temples to female fertility have not been found, yet many are the sculptures that celebrate it. This, in broad terms, was the spiritual and religious reality that the Romans found in 200 BC when they succeeded, and it was not easy for them, to conquer western Liguria. The Romans, as always and everywhere, did not impose their religious rituals and beliefs, but merely added them to those already existing in the occupied territories. The innovation brought by the Romans was that deities, originally impersonal and cosmic, acquired personalized and anthropomorphic identities, similar to the following Christian religion. Already widespread in Turkey and in the Horn of Africa, Christianity - defined by the Sanhedrin as an "impious sect of Judaism" - after Nero, after the first Jewish war and after the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem, found growing favour among the various Roman social classes, including the political and military ones.

The most sanguinary historic persecutions of Christians were perpetrated in the 3rd and early 4th centuries when Christians had by then become numerous and rich, while the empire - overwhelmed by an unstoppable cultural, military, political and economic decline - was increasingly in search of new financial resources and accepted money (the currency of that time, i.e. sesterzi) in exchange for "vital" amnesties. This concurrent cause also finds its space in history.

To the pagan erratic polytheism, the Romans preferred merciful Christian monotheism and faith in eternal life. The effective missionary work of all converts and presbyters (at that time not priests) favored evangelization: many Christian Roman soldiers spread their faith throughout the empire. Thus even the western part of Liguria knew the first evangelizers.

Tradition has it that among them there was the Milanese of Jewish religion San Nazario, a disciple of San Pietro, who - with San Celso - arrived as far as Provence. Both were then martyred in Rome at the end of the 60s AD. As mentioned, they preached monotheism and professed to be disciples of Christ, the Messiah, the incarnate God, dead and risen to eternal life. As theological points of reference they had the testimonies handed down verbally, the first apocryphal gospels, the sacred scripture, and natural law.

With the edict of Constantine of 313 and the subsequent historical events, Christianity assumed great political power, and of the power it adopted the principles that have always and everywhere been consistent with this role: behavioral decalogues, dogmatisms, deterrent punishments, rites and aggregating functions. The original principles of absolute trust in God, of love for oneself and one's neighbor did not seem sufficient to consolidate religious affiliation.

For power to function it was also essential an organized, centralized, efficient, interdependent and widespread presence on every known land. The first protagonists of the evangelization organized in the Ligurian west were the monastic religious orders. Already at the end of the fifth century, some hermits had found refuge in the various islands of the coast (Lerins, Gallinara, etc.) devoting themselves to meditation and prayer.

On the island of Lerins, opposite Cannes, many gathered and formed large cenobitic communities with abbots and rules. It is said that it was on this island that St. Patrick, the evangelizer of Ireland, would have completed his studies, but there is only evidence that the monastery was frequented by Irish and Scottish pilgrims. In 732 the abbot and five hundred monks, attacked by the Saracens, were killed. In 1073 the monastery was rebuilt and fortified by the abbot Aldebert.

These centers of religious, cultural and political studies, spread gloriously in France and throughout Europe, were the embryos of the great medieval civilization. The monks practiced, among other things, celibacy, the mortification of the flesh and the individual confessions, practices and canonical norms still in existence today.

The abbots, elected by all the members of the communities, exercised an independent power, even superior to that of the bishops, so much so that Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, crowned in 800 by the Pope, confirmed properties and privileges to religious institutes (such as the collection of tithes) and to the abbots (by right also councilors of the crown).

The military management of the empire, on the other hand, was organized according to the feudal principles of the hereditary noble classes whose institutional obligations were loyalty to the emperor and defense of the communities entrusted to them; the inhabitants of the territory paid the tithes of their crops for this service.

In western Liguria, unlike many other Carolingian territories, the nobles were not owners of the land (exceptionally, some had only oil mills and transit rights); their right was to collect tithes on every economic activity carried out by the populations and on the assets of the citizens. They lived in castles and commanded armed troops to guard communication routes and civil and religious properties.

The assignment, therefore, of a lordship (frequently a noble exercised this authority) consisted in the transfer of a right, not of a territorial property, which instead belonged to the local heads of families, the land owners.

The year one thousand was the year of a general economic, demographic, cultural and social revival of the whole of Europe. From a religious point of view, it was the German popes, appointed by the Saxon emperor Otto III (cesaropapism) who marked indelibly the ecclesial structure of the Church (it took another thousand years to see another German, Benedict XVI, climb the sacred throne).

Gregory V, son of the Duke of Carinthia, in fact, with his reform affirmed the primacy of the bishop of Rome and of the Holy See over any other authority, whether they were abbots, religious orders, territorial bishops or clergy, upsetting the status quo and defining the organizational principles that are still in place today.

In Europe, in Italy and in west Liguria, the Church acquired a widespread and verticalized structure with the dioceses and the parishes as custodians and executors of centralized decisions. Religious autonomies and local identities, in fact, were all abolished.

From a political point of view, instead, some individual and local rights found "formal" recognition with the promulgation of municipal statutes: in "practice and in fact", however, power was always exercised by autocratic potentates.

In most of the Ligurian west, it was the Republic of Genoa that assumed political, economic and cultural dominance. The economic subjugation of the Ligurian west to Genoa was irreducible: Savona, Ceriale and other towns know it very well, since they saw their ports buried only for having tried to promote initiatives in competition with those of Genoa.

Many Ligurian westerners were also forced to embark and fight following the Republic of Genoa in the Crusades promoted by the Popes in support of the project to militarily compose the Byzantine schism and to liberate the holy places. Historically, external conflicts are used to reinforce internal consensus.

Always, sailing in the Ligurian Sea and in the Mediterranean required particular attention to pirate attacks, but - after the Crusades - pirate attacks at sea and on the coastal cities intensified so much that it has been hypothesized, without any real evidence, that the incursions of the new pirates (called "Saracens" or "Turks"), had actually been retaliations to the Christian crusades.

It is a fact, however, that the monasteries on the western Ligurian coasts and the coasts of Nice were destroyed by the Muslims before and after the Crusades and that their raids on the coast became so frequent and cruel that many inhabitants of the coast took refuge inland in more defensible small communities and villages.

These micro communities still characterize today part of the western Ligurian society and represent its charm and its problem.

Despite all the difficulties and the passage of time, Christian religion remained indissolubly the "religion of the people". Participation in the cult was general, both by belief and by custom. Every few houses there is still today a church, an oratory, a place of worship. On the facades of the buildings, in the alleys, at the edge of the mule tracks, everywhere, you can see aedicules, portals, niches and crosses: almost always built on private and voluntary initiatives, so as to certify that this faith, practiced by the vast majority, offered to that humanity satisfying answers to its questions for a meaning.

Shared was a generalized belief in the relationship of the living with an afterlife of the deceased. In the hinterland the cult of the dead is still practiced: funeral ceremonies are often mass popular events.

The Church, responsibly, had assumed, directly and indirectly, also the task of supporting different forms of social assistance and the confraternities were for centuries a religious conscience and a work of solidarity in every small or large community of western Liguria. The relief from suffering, death and loneliness, in fact, was the institutional purpose never betrayed by the confraternities.

The average life, at that time less than 40 years, the hardness of work in the stony and arid areas, the inaccessible logistics, the orographic configuration of the arable land, explain the reason why in churches, homes, confraternities, everywhere the Christian symbol - which was originally the fish - was confirmed to be the Cross, which implies the interpretation of life as an offering of immolation rather than as a joyful divine gift. That was not the time to talk about the joy of living; the greatest joy then, perhaps, was to generate lives and build large families.

A concrete comfort, again, came from religious brotherhoods. In case of illness or impossibility to work, it was customary for the confraternities to contribute free of charge to the cultivation of the fields and to the care of the relative harvest on behalf of the disabled person.

The world, meanwhile, all around, was running: culturally, economically, socially, religiously. The message of the Enlightenment ("the super-Christianization of being", according to Voltaire) exploded first among the European intellectual classes and, with the occupation of the Ligurian west by Napoleon's troops, it reached the western Ligurian city-society. The secular socio-economic-political-philosophical-religious immobilism was wiped out in a few weeks.

All the sovereignties of Liguria (counties, marquisates, principalities, communes, the Republic of Genoa itself) became, directly or indirectly, part of the French Empire and adopted its revolutionary constitution. The religious orders were abolished, the monasteries were closed, their properties confiscated and destined to civil purposes, the schools were handed over to the municipalities. In the logistically isolated valleys, the effect of the new thought was contained, almost irrelevant.

After the Restoration, the secular clergy recovered, in some way, its popular prestige; but nothing more. Forever, by then, it had lost its cultural hegemony. The enlightened and liberal world had set in motion, boldly, in search of happiness, no longer in the post mortem, but "hic et nunc" (i.e. “here and now”): freedom, equality and brotherhood.

New powers were immediately behind the new banners. Liguria participated as a protagonist in these new yearnings and its west was a welcoming cradle for many Mazzinians, independentists, Garibaldians and forerunner-socialists: all anticlerical movements.

The Risorgimento, too, was lived and participated above all by the privileged classes of the cities, many of which were adjacent to the Anglo-French Masonry. In the villages the religious practice remained substantially unchanged also thanks to the local defence of the clergy. The absence of secular primary schools slowed the reformist impetus.

The request for reforms remained, however, unavoidable and new forces were pressing.

With the Congress of Vienna of 1815, which also marked the official end of the Holy Roman Empire, the territory from Nice to the mouth of the Magra river, with the subdued Genoa, was assigned to the Savoys - kings of Sardinia and princes of Piedmont. In 1870, the papal excommunication for having ordered the invasion of the Papal State and the capture of Rome was inflicted on the Savoys: in the Ligurian west the religious effects of these facts were practically irrelevant.

Instead, the political and economic powers changed, once very sensitive to the pressures of the ecclesiastical hierarchies, now subjected to the preferential pressures of the new dominant secular and openly anti-clerical groups. It was necessary to wait until 1929 for the Italian governments to realistically recognize the communicative power of the Church in determining popular consensus: thus a compromise of mutual satisfaction was elaborated.

With the Concordat, the Catholic religion was recognized as "State Religion" and the Church was granted, by way of repair, various and remarcable benefits: substantial financial sums, restitution of properties, even those held centuries before, recognition of religious holidays as national holidays, salaries to parish priests, favorable taxes. Western Liguria remained, even in this case, religiously stable and marginal.

The fierce experiences of the Second World War, the German occupation, the civil war and the final reckoning did not substantially affect the historical relations between the Church and the worshippers. In the coastal cities and, above all, in the hinterland, the clergy - with rare exceptions - almost always sided in defense of the inhabitants, whatever their choice of party. Many priests were arrested, imprisoned and shot by occupation troops or by the soldiers of the Republic of Salò.

The 1948 elections witnessed in the Ligurian west a large majority in favor of the Christian Democrats (around 56%) with the blockade of various socialist and communist parties at around 37%. The Church chose to support and rely on, so as to become almost a synonym, the Democrazia Cristiana (i.e. Christian Democracy) with which it shared the international position and the anti-Marxist policy.

This choice, winning in an international perspective, placed the Church and the clergy in the communities of the west, for the first time in centuries, in stark contrast with part of the believers: never in history had the western Ligurian community split like that. It was not until the Ecumenical Council II, the fall of the Berlin wall and the bourgeoisification of the less wealthy people that we could see their mutual aggression mitigated.

The Church, however, had lost its role of super partes and the recovery of this position is laboriously underway. Even the essential confidential relationship of the clergy with the individual believers had weakened, both because of the lack of priests, but also because the massive and vertical structure of the Church leaves no room for the evolution of history, always capable of inventing new instruments suitable for satisfying new needs.

The historical and free presence of religious orders constituted an added value of the evangelical offer, but it is now numerically absent.

Far more devastating effects on the traditional civil, cultural and religious life of the whole Ligurian west has been the impetuous succession of post-war events that are known as the "economic boom" of the fifties.

The diffusion of the media (television, newspapers, periodicals), direct and immediate communications (telephones), individual transports (motorcycles, cars) brought to the homes of everyone realities and opportunities not even imaginable before. It was then that the fascination of economic well-being and the relative gratification in the purchase of goods became an irresistible and insatiable attraction, so much so that it soon became the very purpose of living.

The young people of the hinterland, released from the ancient bonds, immediately realized the opportunities: they left their consenting families without regrets, they forgot the countryside and the historical habits to enjoy, finally, the excitement of living adventurous lives. Behind them they left uncomfortable situations, lonely old people, and definitive demographic declines.

On the coast, the transition was more positive: new buildings rose like mushrooms, everywhere and in any case, rich tourists arrived, and consequently commercial development, ready and fast wealth, new people: as long as they could be there.

The local vernacular (and its inherent culture) stopped being spoken, even in native families.

Affluence included a comprehensive, public, good quality, absolutely non-denominational social and health care system. Hospital care, to which female religious orders had provided nursing services, was soon managed by lay staff, professionally trained and kept up-to-date.

The Church, in the most populous towns, maintained and maintains, with commitment, the essential services: it offers open churches, youth oratories, some schools, sports associations, voluntary assistance activities (San Vincenzo, Caritas).

In the small communities of the hinterland the religious situation highlights, instead, a profound separation with the reality just described. What still remains of religious practice finds more reason in popular attachment to tradition than to a faith constantly nourished, alive and young. In the western Ligurian society, a growing irrelevance of Christian culture is clearly evident.

Aware of this state of affairs, aggravated by the arrest of vocations, the bishops find - to attend at least the most important liturgical celebrations - courageous priests often coming from other cities and from foreign countries. Undoubtedly there is a favorable and growing sense of belonging, not always translated, especially by young people, in attending the various religious practices.

The work of evangelization towards the new inhabitants is not evident, at least at the moment. Many, however, silently await a Good News - ancient and new - still able to amaze, communicated in current language and able to recreate a collective trust in the future.

A poor friar testified his belief by asking that the lamp be removed from the dusty ancient furnishings and put back where it could shine.

Today becomes legitimate the question: "the God who consoled the man created and sacrificed to an existence of indescribable hardships and rationally unacceptable deaths, this same God is still effective when fatigue and physical pain no longer exist, the superfluous dominates in every choice and every private need is covered by public assistance?".

Reality shows clear signs that western Ligurian humanity is looking for new support (impalpable, spiritual?) to counteract its existential discomfort. Is the Christian message back, the one lived in the villages of the hinterland for centuries, which included not only the saving word of God, but also the deafening silence of God?

The British Psychological Society defines this state of mind as "the anorexia of the future".

The civil society responsibly realized the problem and made public structures and scientific medical services widely available. There are also many private studios that practice methods of "meditative spirituality", usually of oriental inspiration.

The use of psychiatric drugs is a common therapy for the inhabitants of small inland communities. The predictions and hopes had been different. No one imagined that a future of economic well-being like today, compared with yesterday's cruel poverty, could ever be the prelude of a profound collective alienation. The Church also experienced this alienation. Its path of recomposition is impervious and innovative: from the centrality of the old behavioral norms to the centrality of the spirit that speaks to the people of God.

The prior of an ancient and glorious confraternity confided his ambitious projects to the confreres: "Fire smolders! There we are, an evangelical resource loved by all; we live a journey of faith in God, with the people and with the church, we are independent, we keep our places of meeting and worship with our contributions, we are present in the works of assistance and charity, we elect our "priors", we do not separate ourselves by census, erudition, political opinions and age".

Has this patrimony of the religious history of the Ligurian west remained a raceme, forgotten by hasty harvesters? And yet, it is also in these ancient and current testimonies of popular spirituality that one can sense the identity of the Ligurian west, a gift to contemporaries.

* The priest and poet of the valleys was an old man who understood the value of the gift of a life of faith and the limit of the codes. So he prayed: "Sometimes, on stormy nights, you have to let go of the moorings and free the fleets by challenging the hurricane in the open sea. That's when I ask Him: why don't you take the helm of the captain ship? The crew already shakes the lanterns towards the stars. For each other, we will sail together towards dawn, breaking the curtain that separates us from the sun".